This is part of her excellent obituary, by Jim Jump, in the Independent (hyperlinks added):

Mary Low was a poet, linguist and classics teacher who, as a 24-year-old Trotskyist, vividly described the revolutionary fever that gripped Barcelona in the months following the military uprising against the Spanish Republic in July 1936. The era ended in May 1937 when the Republican authorities suppressed the city’s anarchist and dissident Communist movements.

Low’s Red Spanish Notebook: the first six months of revolution and the civil war (1937) was jointly written with her Cuban husband, the Surrealist poet Juan Breá, with a foreword by the Marxist historian and critic C.L.R. James. Her contribution consisted of 11 snapshots of mostly everyday life in those extraordinary times – when, as she reported, street barrel-organs played the “Internationale”, shoeshine boys carried an anarchist union card, waiters refused tips and notices were hung in brothels urging the clientele: “You are requested to treat the women as comrades – The Committee (by order)”.

George Orwell praised the book in a review for Time and Tide on 9 October 1937: “For several months large blocks of people believed that all men are equal and were able to act on their belief. The result was a feeling of liberation and hope that is difficult to conceive in our money-tainted atmosphere. It is here that Red Spanish Notebook is valuable . . . it shows you what human beings are like when they are trying to behave as human beings and not as cogs in the capitalist machine.”

This was the scene that Low found in Barcelona’s central thoroughfare of Las Ramblas:

“Housefronts were alive with waving flags in a long avenue of dazzling red. Splashes of black or white cut through the colour from place to place. The air was filled with an intense din of loudspeakers and people were gathered in groups here and there under the trees, their faces raised towards the round discs from which the words were coming.”

She brought a perceptive outsider’s – and Anglo-Saxon – eye to convey the quirks of life in “red” Barcelona, avoiding the heavy-handed heroics of some of her contemporaries. She notes, for example, the bureaucratic culture of the politicians and functionaries of the Catalan government in contrast to the egalitarian mood on the street. She visits the deserted suburb of San Gervasio, its fountains still playing in the gardens of the locked villas where the city’s rich families once lived.

There is no pomposity or romanticisation in her account of the burial of the anarchist leader Buenaventura Durruti, killed in November 1936 leading his militia in the defence of Madrid. His funeral, attended by tens of thousands of supporters, was delayed because alterations had to be made after it was discovered that the tomb for his coffin was too small, as was the pane of glass for viewing his embalmed corpse.

Newly arrived in the Catalan capital, she was horrified to find that the siesta was still being practised. “Do you mean to say that you shut up everything and go to sleep from one till four during the revolution and civil war?” she and Breá asked one inhabitant incredulously, only to note: “He stared at us from large languid eyes as if the sun had struck us.” Equally dispiriting for her was the continuing enthusiasm of the locals for the lottery – “the eternal lottery, like a veil of illusion still preserved for Catalan eyes”.

Born in London in 1912 to Australian parents – her father was a mining engineer and her mother a former actress – Low was educated in France and Switzerland. She mixed in circles frequented by left-wing political activists and avant-garde artists in Paris, where she met Breá in 1933. Among their friends were André Breton, Paul Eluard, René Magritte and Yves Tanguy. They travelled around Europe and to Cuba, eventually making their way to Barcelona in August 1936, where General Francisco Franco’s revolt had been crushed by workers’ militias and elements of the armed services loyal to the Republic.

Like Orwell, Low and Breá joined the quasi-Trotskyist POUM (Workers’ Party of Marxist Unity). Low worked on the English-language broadcasts for the party’s radio station and helped finance, co-edit and translate its fortnightly English newsletter, The Spanish Revolution. She was also the POUM’s representative in the press office of the Catalan government.

Paul Hampton gives more detail here:

She was part of a talented group of Trotsky-influenced young people, including the surrealist poet Benjamin Peret, Kurt and Katia Landau, Hipólito and Mika Etchebehere, Lois Cusick (Orr) and Charles Orr, Pavel Thalmann and Clara (Ensner) Thalmann, Nicola Di Bartolomeo and Virginia Gervasini, Robert de Fauconnet, Erwin Wolff and Hans Freund who went to Spain to fight for working class socialism. Many paid for their courage with their lives.

Low did radio broadcasts and edited the 8-page English-language weekly newspaper, The Spanish Revolution, from its first nine issues from 21 October 1936 until 23 December 1936. She was responsible for the section “News and notes” and for translating into English articles published in the POUM’s paper, La Batalla.

She and Breá left Spain on 28 December 1936. (The following issue of The Spanish Revolution, Volume II, No1, 6 January 1937 announced her departure.) Breá had been detained twice by the Stalinists and was involved in a near fatal and suspicious car “accident”.

Jump again:

Low and Breá were married in London in September 1937, shortly before the publication [by Secker and Warburg] of Red Spanish Notebook, for which Low translated Breá’s seven chapters from Spanish into English. Following interludes in Cuba and Paris, from early 1938 the couple lived in Prague, where they had several Surrealist friends, until July 1939 when they were forced to leave in the wake of the Nazi invasion.

Low’s poetry first appeared in a joint compilation with Breá, La Saison des flûtes, published in Paris in 1939. Again displaying her skills as a linguist, the poems were written in French and, in “La Chauve-souris visite Marseille” (“The Bat Visits Marseilles”), contain the apparently self-referential lines:

Type standard de l’aventurière internationale

cheveux roux

regard fatale, longue

robe blanche, accent onomatopé

aux surprenantes ambiguïtés harmoniques.In 1940, Low and Breá boarded a transatlantic liner in Liverpool and made their way to Cuba, where she would remain for the next 25 years. Breá, however, was already ill and died just over a year later. In 1943 in Havana Low published a selection of essays, La verdad contemporánea, on political and cultural themes which featured a foreword by the French poet Benjamin Péret, whom she had known in Paris and Barcelona. The essays were edited versions of talks which she and her late husband had given at the city’s Institute of Marxist Culture in 1936 under titles such as “The Economic Roots of Surrealism” and “Women and Love from the Perspective of Private Property”.

In 1944 Low married Armando Machado, a Trotskyist Cuban trade-union leader, with whom she would have three daughters. At the same time she acquired Cuban citizenship, keeping her dual British-Cuban nationality for the rest of her life.

More poetry collections followed: Alquimia del recuerdo (“Alchemy of Memory”) in 1946, illustrated by the Cuban-born Surrealist Wilfredo Lam, and Tres voces – Three Voices – Trois voix in Spanish, English and French in 1957, for which the Cuban artist José Mijares provided illustrations. In 1948 she also translated El rey y la reina, as The King and the Queen, by the exiled Spanish novelist Ramón Sender.

Low and Machado welcomed the 1959 Cuban revolution. She taught English and Latin at the University of Havana and both of them became leading members of the re-formed Trotskyist POR (Revolutionary Workers’ Party). However, the party soon fell out of favour with the new regime. Indeed Machado was on one occasion arrested and only freed following the personal intervention of Che Guevara. Low moved to Sydney in 1965 and in 1967 she and Machado settled in Miami. She taught Latin and classical history at some of Florida’s élite private schools, having been barred from any public-sector teaching posts on account of her background in left-wing politics. She continued her writing and poetry, which were published in In Caesar’s Shadow (1975), Alive In Spite Of – El triunfo de la vida (1981), A Voice in Three Mirrors (1984) and Where the Wolf Sings (1994).

She retired from teaching in 2000 and, until wheelchair-bound in her final year, continued to travel, regularly visiting and making new friends in Europe, with whom she enjoyed telling anecdotes from her eventful life.

JJ Plant adds, in relation to her later years:

She worked closely with the Surrealist tendency associated with Franklin Rosemont….

In October 2002 she was one of the many signatories to the Surrealist-sponsored declaration Poetry Matters: On the Media Persecution of Amiri Baraka. Her final militant act was to sign a declaration of critical historians opposing the dominant historiography that depicts the Spanish revolution simply as a struggle between fascism and anti-fascism, (exemplified by Hobsbawm among UK academics) and seeks to erase the struggle between the classes from the historical record.

Mary Low’s ashes were scattered in Cuba and in Paris.

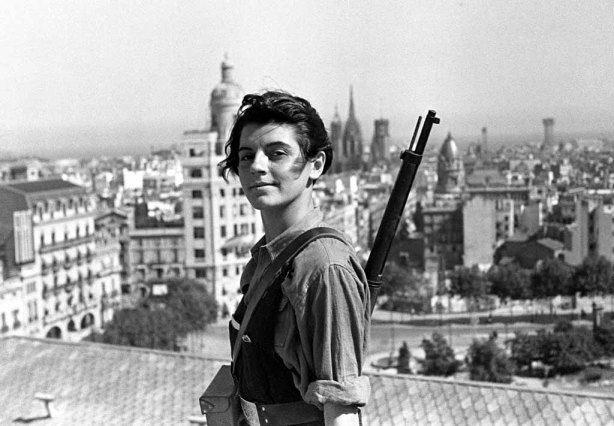

Some further sources and image from this wonderful Cezch website:

GUILLAMÓN, Agustín. Esbozo biográfico de Juan Breá. La Bataille socialiste [webové stránky], 2010 (původně otištěno v časopise Balance, noviembe 2009, no. 34).

GUILLAMÓN, Agustín. Mary Low, poeta, trotskista y revolucionaria. La Bataille socialiste [webové stránky], 2009.

GUILLAMÓN, Agustín. Perfiles revolucionarios: Mary Low y Juan Breá. Iniciativa Socialista [webové stránky] (původně jako předmluva ke knize Mary Low a Juana Breá Cuaderno Rojo de Barcelona /Barcelona: Alikornio, 2001/).

Juan Breá. In KELLEY, Robin D. G. – ROSEMONT, Franklin (eds.). Black, Brown & Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2009, s. 55-58.

JUMP, Jim. Mary Low. The Independent, January 30, 2007.

ROCHE, Gérard. Mary Low (1912-2007) (materiál kombinuje autorovy texty otištěné v knize Mary Low Sans retour: Poèmes et collages /Paris: Syllepse, 2000/ a v bulletinu, vydávaném Sdružením přátel Benjamina Péreta, Trois cerises et une sardine, novembre 2007, no. 21).